|

| Lord Leighton : Cimabue's Madonna |

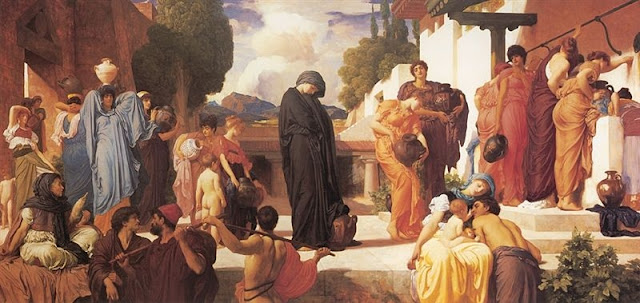

The title of this piece is a quote from none other than Queen Victoria and is a handy way to refer to a painting by Frederic, (later Lord) Leighton (1830-96) the full title of which is "Cimabue's celebrated 'Madonna' is carried in procession through the streets of Florence; in front of the 'Madonna', and crowned with laurels, walks Cimabue with his pupil Giotto; behind are Arnolfo de Lapo, Gaddo Gaddi, Andrea Tafi, Nicola Pisano, Buffalmacco, Simone Memmi. In the right corner is Dante."

Somewhat of a mouthful I am sure you will agree and for obvious reasons it is usually just referred to as "Cimabue's Madonna". In defence of the original title though, and by way of a little digression, it should be noted that it is a curious fact that pictures and their titles are easily separated, unlike books the title of a picture rarely, if ever, appears on the work itself and it often takes a lot of scholarly research going back through exhibition catalogues or dealer's sales records to match the picture to the title. Indeed most of the pictures known today painted by the old masters before the eighteenth century are known by titles given many years, sometimes centuries later, Leonardo's "The Virgin of the Rocks" and Velasquez's "Rokeby Venus" being just two examples that spring instantly to mind. Thus in the nineteenth century "titles" were often in reality rather "descriptions" in order to prevent any subsequent confusion. The painting by Turner known today simply as "The Slave Ship" but originally exhibited as "Slavers Throwing overboard the Dead and Dying - Typhoon coming on" is another famous example.

But to return to Leighton's picture, the reason for writing about it today is that yesterday I had the pleasant experience of being able to inspect it closely for the first time. The painting usually hangs above the archways of the main entrance at the National Gallery in London and requires one to climb the staircase towards the main galleries and turn round into the traffic as it were and view the painting form a distance of 15-20 metres. Now however it has been hung in a room usually reserved (I think) for impressionist or perhaps post-impressionist work but now re-hung with romantic painting from the late eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. Leighton's picture dominates the room as indeed it would any room if for no other reason than its size, it is a colossal picture measuring 222cm x 521cm, which in old money means its about 7feet high by 17feet long. As Leighton commented to a friend when he sent it in the Royal Academy show of 1855 "at least they wont be able to ignore it".

|

| Lord Leighton : Cimabue' Madonna (Detail) |

Leighton painted the picture in Rome and was unusual amongst English artists of the time in being trained abroad. His grandfather had been court physician to the Tsar of Russia and his father, also a doctor, spent most of his life travelling around Europe seeking a favourable climate for his sickly wife and the best education money could buy for his only son. Leighton therefore studied briefly in Florence and then more extensively in Germany with the Nazarene painter Eduard von Steinle. When he submitted this picture to the Academy he was therefore virtually unknown in Britain and subject to a certain amount of insular prejudice from which he recovered only slowly.

Thus it was that when Queen Victoria and Prince Albert attended the Academy opening as was their custom both picture and the artist were unknown to them. Both, however were hugely impressed as Victoria noted in her diary: "It is a beautiful painting, quite reminding one of a Paul Veronese, so bright and full of light. Albert was enchanted with it - so much so that he made me buy it." The picture remains to this day in the Royal Collection but is on a long term loan to the National Gallery.

|

| Lord Leighton: Cimabue's Madonna (Detail) |

It was a wonderful experience to examine it closely; it really is an extraordinary piece of work particularly when one remembers that it was the first work Leighton had exhibited in England and he was only 25 years of age at the time. Given that, it is a remarkably mature work and one which was to set the stage for Leighton's career. Over the years he produced a big set piece procession picture of this sort roughly every decade, the last being the magnificent "Captive Andromache" which now hangs in Manchester City Art Gallery and is the key work of the latter part of his career just as the "Cimabue" is of the early part.

|

| Lord Leighton: Captive Andromache |

|

| Lord Leighton: Cimabue's Madonna (Detail) |

As the long title explains the picture shows an event narrated by Giorgio Vasari in his celebrated mid 16th century work "The Lives of the Painters" when the people of Florence were so enamoured of the seemingly miraculous work by Cimabue that they went en fete and carried the picture now known as the "Rucellai Madonna" to its resting place in the Church of Santa Maria Novella. Leighton depicts many of the famous personalities of that time. Cimabue himself is the slightly isolated figure in white in the centre, the young boy with him is Giotto who would surpass him as the great genius of the age. Dante looks on from the edge of the picture, fittingly. as he remarked on this passing of the torch of fame from one to the other in his great work the Comedy.

|

| Lord Leighton Cimabue's Madonna (Detail showing Dante) |

The determination of Leighton to make a sensation with this picture is obvious. Not just its size but its glorious colour mark it out as exceptional. Close to one can fully appreciate the individualised heads of all the characters and the beautifully painted draperies and accessories. Originally the figures moved continuously from the right to the left of the picture but when it was nearly complete and two years labour had been spent on it, it was suggested to Leighton that frieze like composition was a bit static and laborious. After some consideration Leighton concurred and wiped out the whole left side to repaint the figures turning towards the viewer. Knowing how difficult it is to change the slightest thing in a picture of mine if I consider it reasonably well done I can only admire with awe this dedication to the pursuit of perfection, a dedication which Leighton pursued throughout his career.

|

| Lord Leighton: Cimabue's Madonna (Detail) |

I don't know if the picture's new position is permanent or only temporary. It has been replaced in its original place by a work by Puvis de Chavannes "The beheading of John the Baptist" a smaller but still very striking piece. Undoubtedly it will enable more people to see it and appreciate Leighton's talent, he is still under appreciated even in this country and even more so abroad. Ironically a man who struggled to win acceptance in England in his lifetime because of his foreign education and training is now seen as archetypically English and amongst European art lovers that can still be a term of criticism. However as always the best thing to do is study the work and come to your own decision, thankfully with this rehang, doing so has just become that little bit easier.